For decades, El Salvador has suffered from street gang violence (the so-called maras), which became deeply entrenched in society after the civil war. In the 1990s, as the war ended and mass deportations of gang members from the U.S. began, criminal groups rapidly gained influence in the country. The largest are Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 (18th Street), which originated among the Salvadoran diaspora in Los Angeles and were brought back to El Salvador through deportations. Besides them, there were smaller groups like La Máquina, Mao Mao, and Mirada Loca. As of 2020, the number of active gang members was estimated at 60,000, and the number of sympathizers or “collaborators” at about 400,000. These gangs filled a social vacuum, recruited disadvantaged youth, and quickly spread their influence to many areas of the country.

The criminal activity of the maras covers extortion, illegal drug trade, murders, and the terrorizing of residents in controlled neighborhoods. For example, gangs charge the population “renta” – a fee for “protection” of businesses – and harshly punish disobedience. In the peak year of 2015, El Salvador’s murder rate reached 103 per 100,000 people – one of the highest in the world. The influence of the gangs was felt even in politics: criminals would ban candidates from campaigning in “their” areas and boasted that they could influence election results. In response, the authorities took tough measures: back in 2003–2004, “Mano Dura” (“Iron Fist”) operations led to mass arrests of suspected gang members. In 2012, the government brokered a temporary truce with MS-13 and Barrio 18, which reduced killings, but the truce collapsed two years later. In 2015, the Supreme Court designated both gangs as terrorist organizations. However, fully reining them in was impossible until very recently.

El Salvador’s Street Gangs: History, Structure, and Activities

Origin and Expansion. Most Salvadoran gangs originated abroad: Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Mara 18 were formed in the poor neighborhoods of Los Angeles in the 1980s among Central American immigrants fleeing the civil war. After the conflict ended, the U.S. deported thousands of criminals back home, which led to the transfer of structured gangs to El Salvador. Once settled back home, the “mareros” (gang members) quickly recruited local youth from marginalized backgrounds, filling the void left by the lack of state support. The gangs are divided into cells (clicas – “cliques”), each controlling a specific territory and bearing its own name. For example, MS-13 includes cliques like “Park View Locos,” “Leeward Criminals,” etc., whose tags can be seen in graffiti on neighborhood walls.

Structure and Influence. El Salvador’s street gangs have a hierarchical structure. The top leadership is often incarcerated and transmits orders “to the outside” through intermediaries. Ordinary members are grouped into small cliques that operate locally. Each gang has its own symbols, nicknames, and a strict code. The main sources of income are racketeering (extorting “protection” fees from business owners and residents), drug trafficking, robberies, car theft, and other crimes. The gangs not only compete with the state but also fight each other (primarily MS-13 against Barrio 18) for spheres of influence. At the height of gang activity (the 2010s), the daily lives of millions of Salvadorans were under their control – many neighborhoods were considered “red zones” where outsiders entered at their own risk.

Gang power is maintained through terror. Disobedience is met with brutal reprisals: murder, torture, kidnapping. The gangs also impose their own “rules” of behavior on residents – for example, introducing curfews and regulating youth relationships. The presence of the maras is visible everywhere: neighborhoods are covered in their graffiti with numbers (“18,” “13”) and gang abbreviations, young people wear distinctive tattoos and use hand signs to indicate gang affiliation. For a long time, the authorities could not provide an adequate response: prisons were overcrowded, and corrupt officials often made secret deals with gang leaders. Nevertheless, by the 2020s the situation had become so critical that the government decided on unprecedented measures to eradicate organized street crime.

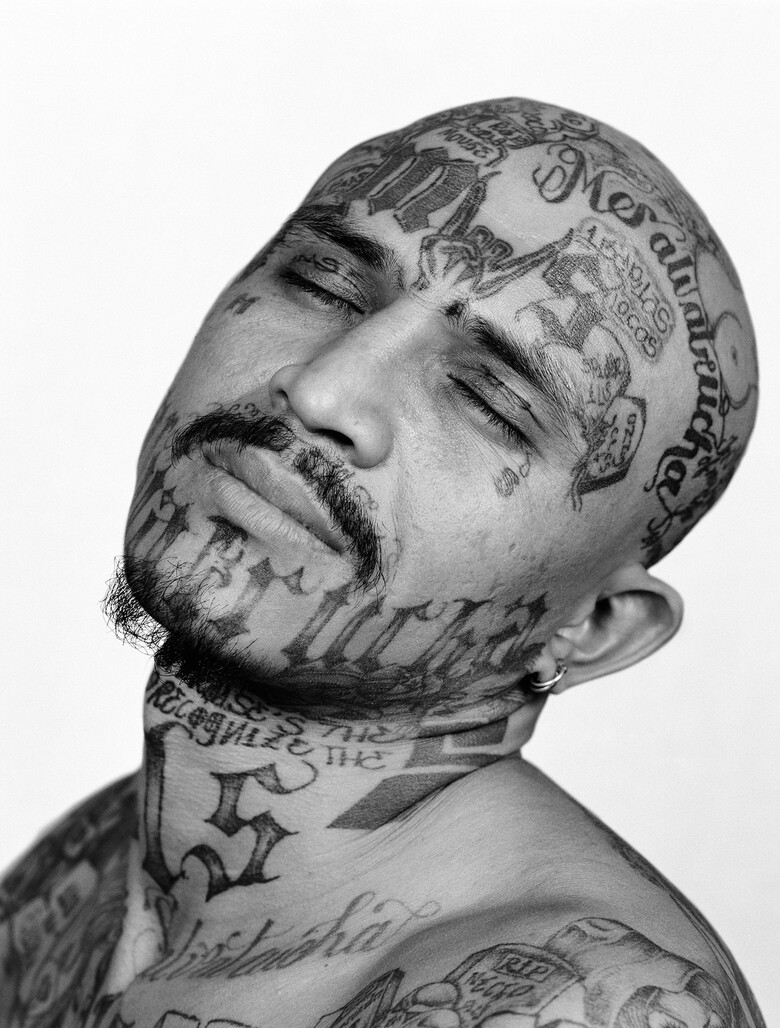

Distinctive Gang Tattoos

One of the most recognizable attributes of Salvadoran street gangs is their tattoos. Tattooing among the maras became a tradition, reflecting identity, loyalty, and a gang member’s “combat history.” Historically, in Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18, there was an unwritten rule: a newcomer had to get the gang’s symbols tattooed, thereby “branding” themselves before society. Popular designs include large letters and numbers (such as “MS,” “18,” or “X8”), Gothic script with gang names (Salvatrucha, Dieciocho), images of skulls, demons, crossed machetes, and other intimidating motifs. Each tattoo has meaning: it can indicate rank in the gang, the number of “jobs done” (up to and including murders), a particular clique, or a significant event.

For example, the image of death with a scythe among Barrio 18 members symbolizes a readiness to kill and die for the gang, while a spiderweb represents power and expanding influence. Tattooed abbreviations, slogans (“Mi vida loca” – “my crazy life,” shown as three dots in a triangle), and religious symbols are common: for example, the Virgin of Guadalupe for Barrio 18 (a nod to the group’s Mexican roots), the face of Jesus with hidden “MS” letters for Salvatrucha. Some signs are purely practical: barbed wire on the skin means a long prison sentence and loyalty to the gang even behind bars.

In the past, gang members covered their entire bodies, including their faces, with tattoos, openly displaying their affiliation. MS-13 fighters, for example, became known for their inked faces and the number “13” on their forehead or neck. However, in recent years, things have changed: visible tattoos have become unnecessary and even undesirable. Under pressure from tough anti-gang measures in El Salvador and neighboring countries (where just a tattoo could get you arrested on suspicion of gang involvement), leaders ordered an end to the practice of visible tattoos. Many young mareros now only get tattoos under clothing or skip them altogether to avoid police attention. Still, among the older generation, you can find people whose bodies are almost entirely covered in tattoos, telling the story of their “career” in the gang. The tattoo remains an important symbolic ritual – a sort of “passport” for a marero, a visual sign of lifelong attachment to the criminal “family.”

Interestingly, tattoos are used not only for self-expression and intimidation but also as a means of communication. Experienced law enforcement officers have learned to “read” tattoos: they can determine a person’s affiliation with a particular clique, specialization (for example, a drawing of a prison tower can mean the wearer oversees order in prison), or even the gang member’s personal nickname. However, such open information worked against the gangs – authorities, identifying maras by their tattoos, became more effective at tracking their movements and connections. As a result, the era of flashy tattoos is gradually fading, giving way to more subtle symbolism. Nevertheless, the legacy of this culture is firmly embedded in the image of Salvadoran crime: the images of the numbers “18” or “MS-13” on walls and bodies remain a grim reminder of the years when gangs freely terrorized the country.

The New “Super-Prison” for Gang Members

In 2022, the government of El Salvador, led by President Nayib Bukele, launched an unprecedented campaign against street gangs – the so-called “guerra contra las pandillas” (“war against gangs”). The trigger was a surge in violence in March 2022, when gangs killed 87 people in a single weekend, setting a grim record for the highest number of murders in a day since the war. Bukele secured the introduction of states of emergency (Estado de Excepción), which allowed suspects of gang involvement to be arrested by the thousands without warrants or charges. In a year, such arrests exceeded 60,000. Facing overflowing prisons, the authorities decided to build a new, huge penitentiary facility specifically for holding mara members.

Construction began in mid-2022 on a fast-track schedule, and by January 2023 the complex was ready. The new prison was named the Terrorist Confinement Center (Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, or CECOT). It is located in an isolated area – in the municipality of Tecoluca, San Vicente department, at the foot of the San Vicente volcano. The scale of the facility is unprecedented: the complex covers 23 hectares, surrounded by a guarded zone of about 140 more. The fortress walls, in several layers and 11 meters high, are topped with barbed wire, the perimeter is guarded by 19 watchtowers, and electric fences are set up at the corners. Inside, there are eight cell blocks, with a total capacity of 40,000 inmates. This makes CECOT the largest prison not only in El Salvador but in all of Latin America. Designing and building the complex cost the treasury about 100 million U.S. dollars – an enormous sum for a small country, justified by the extreme crime situation.

The first group of prisoners – 2,000 accused of gang membership – were transferred to CECOT in February 2023 under the strictest secrecy and heightened security. The prison quickly filled: by June 2024, it held 14,532 people, and by the end of 2024, the number reached 20,000 (about half the designed capacity). In fact, CECOT became the place of isolation for most of the mara members arrested during Bukele’s campaign.

Conditions in the new prison are extremely harsh. Prisoners are housed in shared cells of about 100 m², with each cell averaging 65–70 people – less than 2 m² per person. Each cell has 80 metal bunks, but no mattresses or bedding. The cells are lit by bright lights that never go off, 24 hours a day.

Each cell has only two toilets and two sinks, explaining the extremely unsanitary conditions amid overcrowding. Inmates’ food is meager – beans, corn porridge, rice, and eggs, served twice a day. They are not given utensils (for security reasons). Outdoor exercise, family visits, and phone calls are prohibited – inmates spend virtually all day locked up, leaving their cells only briefly for rare video meetings with judges or for disciplinary and demonstrative movements around the territory. The administration announced that there are no rehabilitation programs or sentence reviews for these inmates: according to Justice Minister Gustavo Villatoro, “these criminals will never return to society.” Effectively, it’s life imprisonment with no chance of release – this is the government’s approach to gang members in CECOT. To maintain order, a large force has been mobilized: the facility is guarded around the clock by 600 soldiers and 250 police officers.

The regime in the “mega-prison” is extremely tough, which has drawn both praise and criticism. Supporters of President Bukele note that, finally, thousands of murderers and extortionists are isolated from society – the prison has become the physical embodiment of the state’s victory over the maras. On the other hand, human rights advocates sound the alarm: mass arrests were often carried out without sufficient evidence, and holding people in such overcrowded dungeons amounts to torture. There have been reports of inmate deaths from disease and lack of medical care. Families of the arrested complain that they have not heard from their loved ones for months. International organizations (Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, etc.) accuse El Salvador’s government of violating basic human rights in the name of a questionable “quick victory” over crime. Bukele himself rejects the criticism, stating that protecting law-abiding citizens’ lives comes first and pointing to a sharp drop in murder rates – in 2022–2023, this figure fell to a historic low. Indeed, according to official data, in 2023 El Salvador was no longer ranked among the world’s most dangerous countries – largely because tens of thousands of active mareros are now behind bars.

Bukele’s uncompromising campaign against street gangs has radically changed the crime situation in El Salvador. At the beginning of 2025, more than 70,000 alleged mara members were in custody – essentially, a whole generation removed from the world of organized crime. Streets once controlled by gangs are gradually returning to state control: murder rates have dropped, and extortion pressures on businesses have eased. Many Salvadorans, for the first time in years, feel a sense of relative safety in their neighborhoods. However, such a “victory” has come at a high cost. The country still operates under a state of emergency, in which citizens’ freedoms are seriously restricted, and security forces have expanded powers. Prisons are overcrowded, and the situation in CECOT is evidence of that. Human rights advocates fear that without addressing the social causes of gang violence – poverty, unemployment, lack of opportunities for youth – the harshness of the repressive system may lead to new problems in the future.

Nevertheless, El Salvador’s experience is already attracting attention from other countries in the region. The term “hacer un Bukele” (“to do a Bukele”) has become a catchphrase meaning a tough anti-crime policy. Neighboring governments are studying the Salvadoran model – from total crackdowns to building ultra-large prisons – as a possible recipe for fighting their own criminal groups. Nayib Bukele himself, whose approval rating soared thanks to his war on gangs, has declared his intention to continue until the maras are eradicated. It’s too early to judge the long-term results of this strategy. One thing is clear: El Salvador’s street gangs no longer feel untouchable, and their ominous tattoos and graffiti are gradually fading in the face of a new reality, as the state seeks to regain control of the streets and people’s lives.

Comments (0)