Dragons stay close to human imagination. They return again and again, with new shapes and new meanings, as if the world keeps finding reasons to draw them back. The image looks familiar, almost simple, yet the simplicity is misleading. Behind every depiction lies a mix of beliefs, fears, seasonal rituals, and hopes carried through centuries. Maybe that is why the dragon feels different depending on where you meet it — in China, Japan, Europe, or the ancient cities of Mesoamerica.

What makes the creature last this long is not size or strength. It is the way people attach stories to it, letting it change without losing its core.

Early Traces: When the Dragon First Emerged

The earliest dragon-like figures in China resemble serpents with small horns and a gentle curve in the body. These shapes do not threaten. They combine ideas of water, mist, brightness, growth. Over time the creature gathers a set of roles instead of a single face, which explains its endurance.

Japan’s early vision moves in a parallel direction but shifts toward water. Long bodies, waves, and a sense of motion—those features become the backbone of later tattoo traditions. Here the dragon grows out of weather, not fear.

Europe takes a different path. The dragon becomes something to resist. A force that interrupts order, stepping out of darkness or guarding a forbidden place. Landscape, faith, and folklore merge into an adversary rather than a guide.

A single motif, but completely different purposes.

China: Order, Rain, and the Shape of Authority

In Chinese culture the dragon acts as a regulator. It moves water, shapes clouds, softens or strengthens the seasons. Instead of destruction, it offers balance. The imperial dragon, especially the five-clawed one, speaks of legitimacy and structure — earthly and cosmic at the same time.

Modern tattoos borrow this framework even when removed from their original context. People choose the dragon as a sign of focus, persistence, or upward direction. The visual language fits that meaning: the body of the dragon flows easily across shoulders, ribs, or the spine. It doesn’t impose itself; it finds a path.

A symbol of movement rather than conquest.

Japan: The Dragon as Guardian

The Japanese ryū sits close to water — not simply as a creature that crosses it, but as something that embodies its shifts. Calm to violent, violent to calm. These transitions result in a dragon that protects by watching, not by roaring.

In irezumi, the dragon becomes an anchor for large designs. Clouds provide rhythm. Waves sharpen the sense of direction. The creature’s body ties the composition into one continuous motion. Japanese dragons rarely appear aggressive. They hold back more than they display, and that restraint becomes part of their appeal.

It is a presence, not a challenge.

Southeast Asia and India: Naga and the Edge Between Danger and Protection

In South Asia the dragon dissolves into the figure of the naga — a being that can either harm or protect, depending on myth and circumstance. The story of Vritra, defeated so that water could return to the world, frames the serpent as a gatekeeper of life rather than a mere opponent.

In Southeast Asia the naga leans strongly toward guardianship. It watches temple stairs, borders of rivers, sacred thresholds. Sak yant tattoos depicting Nagas combine mantras, geometry, and elongated curves that echo traditional carving and architecture. The designs may look minimal at first, but their meaning is layered.

These tattoos tend to feel personal. Quiet, deliberate choices rather than outward declarations.

The Middle East: Chaos Given Shape

Mesopotamian stories portray dragons as forces that must be contained, not avoided. Tiamat stands for raw, unshaped power — the kind that existed before the world gained clear boundaries. Her defeat symbolizes not triumph but the act of organizing what was once unformed.

Another figure, the mušḫuššu from the Ishtar Gate, reveals the opposite idea: a creature refined into a herald of authority. Every tile, every line defines a controlled kind of energy. It doesn’t threaten; it announces.

Tattoo culture rarely turns to these motifs, yet the underlying concept — shaping chaos — still resonates.

Europe: Confrontation, Memory, and the Weight of Myth

European dragons carry a long tradition of conflict. They guard treasures, challenge heroes, define the edge of the known world. The legend of Saint George endures because it presents a clear outline: danger, courage, resolution.

But European symbolism is more varied than that. Celtic dragon knots suggest cycles and continuity rather than direct struggle. Norse imagery points toward ancestry, repetition, and the memory of older worlds. Even when the dragon appears harsh or heavy, the intensity fits the role assigned to it.

Strength is not neutral here. It carries consequences.

Mesoamerica: The Feathered Serpent and the Work of Understanding

Quetzalcoatl and Kukulkan do not belong to the same category as other dragons, though the resemblance is unmistakable. They weave sky and earth together — feathers marking connection to the heavens, serpent motion grounding them in soil and roots.

These beings represent knowledge, renewal, and the alignment of human experience with the natural world. Tattoos inspired by the feathered serpent often carry themes of ancestry or transformation. They do not intimidate. They clarify.

Among dragon motifs, this is perhaps the most reflective.

From Myth to Body: How the Dragon Tattoo Evolved

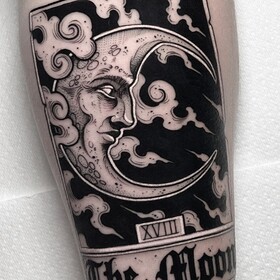

Contemporary dragon tattoos rarely stay inside one tradition. They mix Japanese cloudwork with Chinese motion, European scale patterns with Mesoamerican geometry. The fusion feels natural because the body itself demands adaptation. No human surface is neutral.

Placement changes the creature’s meaning: rising along the spine, circling an arm, or resting quietly across the chest. Scale shifts with intention as well — from monumental pieces to compact symbols.

The reasons vary. Some choose dragons for their cultural weight, some for movement, some simply because the figure feels right when drawn on skin.

The result is a living hybrid, shaped case by case.

A Modern Landscape of Blended Symbolism

Today the dragon is less a myth and more a flexible emblem. Artists merge influences freely. Eastern designs appear in Western contexts and vice versa. Popular culture contributes its own interpretations, but the core remains: a symbol that adapts easily while still suggesting depth.

The dragon becomes a mediator between internal motives and external form. It translates emotion into linework, giving shape to what may be difficult to articulate.

The creature absorbs more than it asserts.

A dragon tattoo no longer insists on power. It suggests direction. Composure. A sense of motion held in place. Whether bold or quiet, traditional or minimal, it keeps the idea of continuity at its center.

This may explain why the dragon has survived across cultures with so many different faces. It adjusts to the person who chooses it. It remains attentive without demanding attention.

And sometimes that is all a symbol needs to do.

Comments (0)